India has about 125 million people who speak English. The number is much greater if you consider those who have at least a working knowledge of English. As is the case worldwide, English has picked up assorted words and expressions from various Indian languages and been bent into localized versions.

If you live in India, you would have inevitably experienced one such version. It may be so ingrained in you that you may not even realize how different it is from English spoken elsewhere. Usage, such as the poem below, may appear normal to the average Indian, but downright comical to those with “refined” ears.

What is your good name, please?

What is your good name, please?

I am remembering we used to be neighbours

in Hindu Colony ten fifteen years before.

Never mind. What do you know?

You are in service, isn’t it?

I am Matric fail. Self-employed.

Only last year I celebrated my marriage.

It was inter-caste. Now I am not able

to make the two ends meet.

Cost of living is going up and up everyday.

Sugar, for example, is costing much.

I am eschewing sugar therefore since last two months.

Also I am diabetes. It is good, no?

Excuse me, please, where are you putting up?

Never mind, you will be coming to my place

one day surely, I am hoping.

Not to disappoint.

You are Madrasi, no? How I make out?

All Madrasis talking English language wonderfully.

I am knowing intimately one Srijut Dandayudhapani

from Brahmanwada.

He is foreign-returned from U.K.

Pronounciation is A1, I am telling you.

Some people are lucky.

He is officer in State Bank, drawing Rs. 2,000.

We are always discussing about politics.

Congress government I am saying

is still best for delivering goods.

What you opine?

Beg pardon, I am going.

I am forgetting to go to Gandhi Market

for purchasing the Aspro

Since today morning I am suffering

from headache pain.

I am taking your leave, yes, for the time.

—R. Parthasarathy

Linguists would expound on the various ways in which Indian English may differ from the Queen’s English. For example, Manfred Gorlach, in “Text Types and the History of English,” lists the following common deviations, which you may have observed in the above poem.

- tense and aspect confusion

- irregular use of articles

- invariable tags (isn’t it? no?)

- questions marked by the intonation, only

- pleonastic uses (headache pain, discussing about)

- local idioms (inter-caste, matric fail, foreign-returned, put up), and wrong uses of British English idioms (make the two ends meet)

- erudite diction (eschew, opine, purchase)

Let’s face it, you may have used or even laughed at the following common expressions:

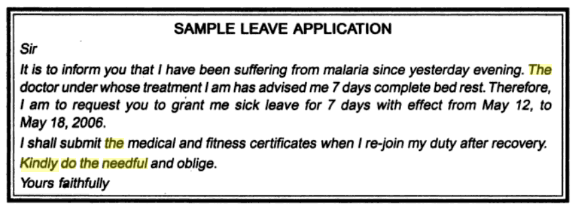

1. Kindly do the needful

This phrase came so naturally to me that I became aware of its being peculiar to India only when I was given this blog post assignment. And why not? It was what we are taught to write in schools and it should come as no surprise that the phrase even appears in Indian books on letter writing!

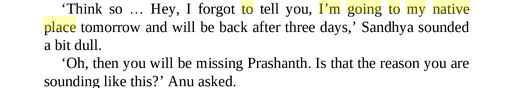

2. I am going to my native

Short for native place, which is the Indian version of hometown, or where one’s family is from.

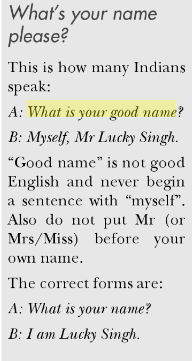

3. What is your good name?

It’s considered polite to ask people what their ‘good’ name is. ‘What’s your name?’ sounds rude and like an interrogation. The phrase is probably a transliteration of the Hindi question, “Aap ka shubh naam kya hai?”

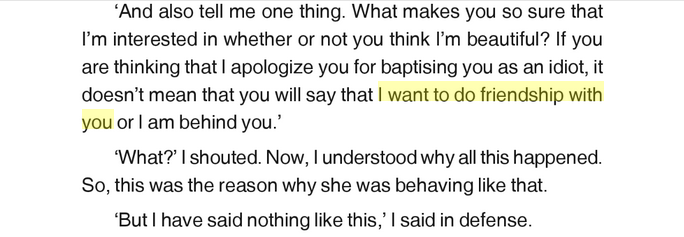

4. I want to do friendship with you

This may be the most annoying one on our list if you were to ask young Indian women and how they get propositioned online. This expression, like the previous one, derives from a transliteration. Blame it on the Hindi expression, “Mujhe dosti karoge?” (“Would you do friendship with me?”)

5. There is no current

When there is a blackout, you might say, “We’ve lost electricity.” Or even, “There is no power.” What most Indians say is, “There is no current.” They may know “electricity,” but it’s always been “current.”

Even the foreign-returned ones adapt and say, “There is no current,” just to be understood. After all, it’s about being pragmatic. When you’re literally in the dark, it is not the right time to be giving illuminating English lessons to those in the dark.

6. No mention

Said as a reply to someone thanking them, “No mention” is a contraction of “Don’t mention it [thank you].” Think of it as a polite, energy-efficient way of saying, “No need to thank me.”

7. Eating my head

If only I earned a rupee for every time I heard a teacher use that expression, I’d never have needed pocket money. It is one more expression borrowed from an Indian language. (Hindi: “Sar kha rahaa hai”)

8. Timepass

It may surprise many Indians, but timepass is not (yet) an officially recognized English word. Nevertheless, the word is deeply entrenched in our vocabulary.

9. Cooling glasses

Ah, it’s so satisfying thinking how many of us have fallen prey to this usage. Our favorite sunglasses from childhood, adoringly called cooling glasses. What a creative expression, conveying both that the glasses keep your eyes cool and also make you look cool.

10. Out of station

Po-tay-to. Po-tah-to.

Out of town. Out of station.

Same thing. Get used to it.

Now for some food for thought. Many of us have laughed at the usage of the above phrases or have been corrected for using them. What exactly is it that makes them “wrong”? Is it merely that the British don’t use them? Granted that it is their language, but every language over the course of history has had to adapt to the needs of its newest speakers when it spread. Following Darwinian theories, if it didn’t adapt, it would die. Much like the grass that survived the storm that felled the great oak, languages have to bend and go with the flow. They pick up new words and idioms, old words pick up new meanings, and take on a life of their own. While some are simply transliterations, others are instances of the language adapting to the local environment. That isn’t reason for them to be looked down upon or laughed at.

The British, while they have popularized their language everywhere, have surprisingly retained the control over what’s kosher and what’s not. They hold the reins and dictate what’s acceptable and what is not. Words like pukka have found their way into the dictionary because the English adopted it, and not because millions of Indians used it as part of their language everyday. Even more remarkably, they have managed to create a stigma of inferiority about anything that is not accepted as part of the Queen’s English, regardless of how widespread the usage is.

Native English speakers brand anyone who doesn’t speak their version of the language as speaking improper English, and it is often an object of amusement for them.

It is illogical that scientific and professional communities (often groups of no more than thousands) are allowed to create a whole new vocabulary and have them accepted into the fold, while ethno-cultural groups (of even millions) are not.

Read on for an example of how, after decades of use by millions of Indians, one creative word was grudgingly accepted into the OED.

Prepone

It’s a shame that it took long for prepone to gain legitimacy. Even greater shame that I still can’t type prepone without its getting underlined in red. The next time one of those oh-so-smart English speakers corrects your usage of prepone or, for that matter, any word/expression from Indian English, forward the following eloquent passage to them.

And even after this minor victory, prepone still carries the stigma of being “improper” English in India, because it was created locally, and not imported from England. It’s time we shook off our colonial hangover and started respecting our identity. We can take a leaf out of the Americans’ book, who simply created their own spellings, words, and expressions in the same language and don’t look to the Brits for approval. Why, I’d love to see the day when Indians mock the British for their quaint, stuffy version of the language.

Featured image courtesy of Adam Cohn

Editor’s note:

Indians also have distinct gestures and hand movements that often confuse westerners and lead to misinterpretations of the gestures. Read about them here: 10 Indian Gestures and Their Meanings.

[…] Now that you have a handle on Indian gestures, want a better grasp of Indian English? Check this out: In Defense of Indian English: Why Prepone Is a Pukka Word […]

[…] If you have been to India, you would have inevitably experienced one or more localized versions of the English language. Read more about Indian English here: Why Prepone Is A Pukka Word. […]