Last night, I came across a young woman’s post on a Facebook group relating to startups in India. She was posting on behalf of a friend, an MBA graduate who had “14 months of work experience,” including at a startup, and was looking for new opportunities… with an “expected salary of 8+ LPA (fixed)”. To those who count in millions and billions, and not in lakhs and crores, that’s short for eight lakh rupees or more per annum (₹800,000+).

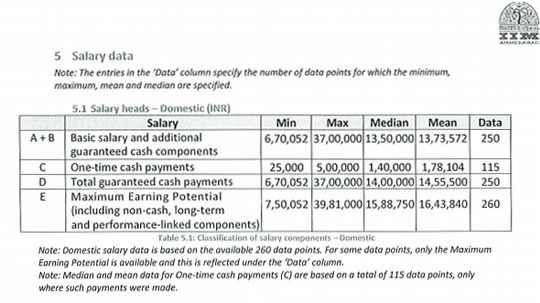

Median Salary Data for Fresh MBA Graduates in India

It didn’t seem unreasonable. The median salary for those graduating from a top-tier Indian MBA program is likely north of ₹15 LPA. Take for example, the data in the table below, which shows 2012 campus placement data at IIM Ahmedabad:

The median salary for fresh graduates of Tier 2 MBA programs (Top 30) in India, if my understanding is right, is in the range of ₹800,000 per year, while those graduating with an MBA from Tier 3 programs (Top 75) receive median offers of ₹4 LPA.

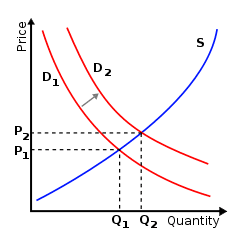

The Laws of Supply and Demand

That young woman’s earnest post seemed to have rubbed some in the group the wrong way. “₹8 LPA with only 14 months of experience?” and “He should stick to his current job” were two of the snarky comments that I noted.

I felt like chiming in with thoughts of my own, but unfortunately, the post seems to have been deleted. If I could still get through to that young woman and her friend, this is what I would say:

I am used to seeing “fixed price” beside fruits, vegetables, and household goods. I can’t recall seeing “fixed [price]” beside a candidate’s expected salary. My take on the situation: While the candidate may be strongly signaling what vendors do – “No bargaining”– it may help to remember that just about everything in life is negotiable. In a free market, the clearing price of a good or service is that which someone is willing to bear and the other is willing to accept.

I am not passing judgment on the expected figure (it could well underestimate the candidate’s worth). I am simply pointing out that there exist laws of supply and demand. If there are no takers at the candidate’s asking price, then his price will have to fall, if he wants a job.

Game of Chicken

In some situations, there may be merit to declaring that you will not negotiate. A government’s signaling that it will not negotiate with terrorists in a hostage situation may result in a short-term loss (of the hostages’ lives). Yet, it may be justifiable as part of a strategy to deter terrorists and thereby to result in fewer calamities in the long run. In another scenario, while driving on a narrow, two-way road little more than one vehicle wide and approaching an oncoming vehicle, yanking the steering wheel off one’s car and visibly throwing it overboard may be an effective ploy to get the oncoming driver to blink and steer his vehicle off course, to make way for you. However, this game of chicken requires the two parties to face off in a deal-or-no-deal situation, which is not the case at hand, where potential job providers haven’t even been identified, let alone engaged in a face-off.

The candidate may benefit from suggesting a high expected salary, both as an anchoring tool in negotiations and as a signal of quality. Stating a “no lower than” salary may help to filter out bargain hunters and save time, but I don’t see it as a way to maximize one’s salary.

Parallels to Startup Funding Pitches

I also want to point out an amusing parallel between a candidate’s fixating on a salary figure and a rookie entrepreneur’s fixating on pre-money valuation while seeking funding for his startup. There are many variables in play in a compensation and funding negotiation. Fixate on only one at your peril.

You may find an employer willing to offer your expected salary, but at what cost?

- How many hours of work will you need to put in every day?

- Would you be expected to work weekends?

- How many days of leave would you get in a year?

- Would it be just one bucket of personal leave or would it be split between casual leave and to-use-only-when-sick sick leave?

- Would the compensation package include medical insurance?

- Would the medical insurance cover just you or your family as well? Would it include dental and vision insurance also? What might required co-pays and deductible limits be?

- What would your prospects be for professional growth?

- To whom would you report?

- Would you get along with your manager? And with your boss’s boss?

- How long would your commute to work be?

- How far, how long each time, and how often would you be expected to travel out of town on work?

- What are likely salary increases and bonuses at the end of the year?

- Would you receive any stock options or equity in the company? If so, on what terms?

Similarly, entrepreneurs hung up on a pre-money valuation may fail to appreciate the impact of many other levers that an investor can adjust in a term sheet. You may get your vanity valuation, but at what cost?

- How many years does the investment fund have left in its life (by which time you will need to return the invested funds, even if it means through a premature, forced sale of the business)? A lower valuation by a fund that gives you more room in which to plan an exit may be a better outcome.

- Would the investment be in multiple tranches, conditioned upon your business’s reaching some milestones? (What if you don’t reach those milestones?!)

- How much runway would you have, to hit your next milestone, by which time you’d have to have become profitable or lined up additional funding?

- Would the fund have enough gun powder (uninvested, uncommitted capital) left to participate in follow-on rounds of funding?

- What signaling risk might you be taking on, in the event that you choose to take an early-stage investment from a large fund that should be able to invest in a subsequent round of funding but decides not to?

- How much liquidity might you see in the funding event?

- How much of the business would you be giving up?

- Would the employee stock options pool be carved out pre-money or post-money?

- How much control of the business, through board seats, would you be giving?

- What downside protections, such as anti-dilution rights and liquidation preferences, would you be agreeing to and on what terms? (This point alone could take up an entire blog post.)

- What vesting period might you have to agree to for your founder’s stock?

Ways to Negotiate a Better Outcome

The way to optimize your outcome, when multiple levers can be pushed in a negotiation, is to look at all of the levers together and to negotiate on the overall package.

While keeping your cards close to your chest, decide on what elements are must-haves and what you’d be willing to concede on and to what degree. Even better, pick up on the elements that are your opponent’s must-haves and what they may be willing to be accommodating on.

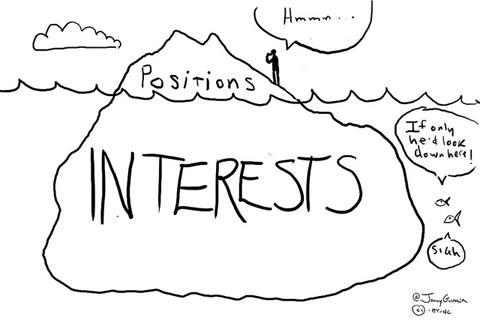

Look beyond your opponent’s stated positions – e.g., “I can offer only ₹X LPA” – and understand their underlying interests. The insights that you gather would be invaluable to negotiating a better and yet mutually beneficial outcome. Their interests may well be, “I want my business to remain profitable” or “I can’t have current employees or other new hires feel shortchanged.” You could then address the underlying interests and concerns and make a case for an outcome that would satisfy your own interests.

Understand that negotiations don’t have to be a zero-sum game. That is, your opponent’s losing ground doesn’t have to be the only way you carve out a bigger share for yourself. Look for ways in which you and your opponent can increase the size of the cake together, before splitting it. Here’s an example: Let’s suppose that your employer’s offer was only ₹7 LPA, whereas you want ₹8 LPA. It would be shortsighted to approach the negotiation as, “For me to gain ₹1 LPA or even ₹0.5 LPA (beyond ₹7 LPA), my opponent will have to go home with that much less.” Think about ways in which you both could improve your outcomes together. Recognize this: If your employer is offering ₹7 LPA, your perceived value to their business may be ₹15–20 LPA (after factoring in overhead). What if, working together at the negotiation table, you and your opponent could agree on ways in which your value to their business were to become ₹20–25 LPA. They would make ₹5 LPA more. What if you agreed on, say, a bonus of 30% on revenues you bring in beyond ₹20 LPA. Your opponent would still make ₹3.5 LPA more, while you get to take home ₹1.5 LPA more.

Be prepared to walk away from the negotiation, and signal that in clear terms, if you are simply not able to get the outcome you desire. Walk the talk, though. Don’t have your opponent call your bluff.

Walking away is easy to do in either of these two cases: You have nothing to lose (as when you’re content with what you have) or you have a competing offer.

It is why professionals who are gainfully employed can demand more when recruiters and companies come calling about new opportunities. If you are open to new opportunities, don’t wait until you’re out of work and have recurring monthly bills that will need to be paid.

It is also why startups that court multiple venture capital firms in a coordinated fashion and are able to get competing term sheets end up raising money on better terms. Rather than an entrepreneur who is running out of cash and has to put himself out there, with a begging bowl, before VCs, be the entrepreneur who can demonstrate traction and a viable business model.

Lastly, be open to being courted, but focus on doing well what you do. (Expand your horizons to do other things if you must.) The better you are at what you do, the more the number of likely suitors and the better their proposed offers. Go about life and become as compelling a prospect as you can. You won’t have to distract yourself as much as when you’re an aggressive chaser of the next opportunity.

PS:

This blog post brought back fond memories of my own MBA program at Chicago Booth. I am grateful to many of the professors there for their lessons on negotiation, managerial decision making, entrepreneurship, and venture capital: Eugene Caruso, Linda Ginzel, John Sylla, George Wu, Scott Meadow, James Schrager, Waverly Deutsch, Ellen Rudnick, Steven Kaplan, Sam Guren, and Ira Weiss. I have also benefited from observing the negotiating and decision making styles of many colleagues and managers over the years, including David Gray, Bruce Hutchison, the late Duane Laible, Rick Strong, and Peggy Noethlich.

Featured image courtesy of Moyan Brenn.

Anil Kumar is the founder and CEO of Jodi365.com. He was previously the first lead associate at Hyde Park Angels. He is based in Chennai and tweets, occasionally, @aktxt.